The Curse of Salt is a series of 12 paintings based on creative research about salt intrusion in Eastern North Carolina, specifically in the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. The paintings are based on photographs, ephemera, and observations I collected in the field. This series weaves together personal observations with a short, narrated history of Buffalo City, ghost forests, highway 64, and the eastern North Carolina region with imagery to create a testimonial about the consequences of human actions and the Anthropocene on the coast, forests, and rivers of Eastern North Carolina. The images include layers of collage, aqueous media, and oil on wood panels.

The Curse of Salt

1

Growing up south of the Dismal Swamp in the Tar-Pamlico river basin I was always afraid of the dark, the woods. I wondered what was beneath the black water stained with tannin that rose and fell under the shade of cypress trees. As a child I spent countless hours crossing swamps, walking logging roads and timber plots with my father, a forester. The woods, swamps, and shoreline were my playground. I know that every square inch of the soil in Eastern North Carolina is haunted; it is soaked in blood, sweat, suffering and struggle. The suffering of Indigenous and African peoples is bound up with the economy that developed along the coasts of Eastern North Carolina after the English colonized the area. Ambitious settlers enacted harmful ideas of dominion influenced by capitalism, Christianity, and white cis-heteropatriarchy. Since then, industries tied to fishing, forestry, tourism, and farming have sought to harness labor and natural resources to build a rural economy. Edwards, Graulund, and Hoglund, in their edited anthology, Dark Scenes from Damaged Earth, write in their introduction, “…the Anthopocene is real in the sense that it produces dramatic and catastrophic climate change, and that it is precisely the affluent section of humanity-the benefactors of capitalism-who have engineered this era…”(xix, 2022). Despite the damage inflicted by humans on this region, this the landscape possesses me. It is beautiful, fecund, and wild. The people, soil, rivers, swamps, trees, insects and wildlife are unique and create an eco-system unlike any place on earth.

2

Rivers are a primary feature of this landscape. The water has always been life-giving as well as destructive, dangerous, and deadly. For centuries, people in this region have endured hurricanes, king tides, wind tides, fish kills, poisonous algae, isolation, shipwrecks, economic downturns, venomous snakes, biting insects, pestilence, flooding, and drought. Before the colonists, there were Algonquin-speaking indigenous people who inhabited the area between the Atlantic and what is known as the Suffolk Scarp. According to Helen Rountree, a renown anthropology scholar of indigenous history in this region, these people were known as the Chowanoke, Weapemeoc, Roanoke, and the Pomeioke. They regularly interacted with the Chesapeake, Nansemond and the Tuscarora. When the English came in the 1500s, they mapped, perhaps incorrectly, all the villages belonging to these people and mangled their names. The indigenous people farmed, hunted, foraged, and fished. Their practices were sustainable and in sync with the seasons and rhythms of the natural world. Eventually, the indigenous people would be pushed out by the white settlers, disease, and scarcity.

3

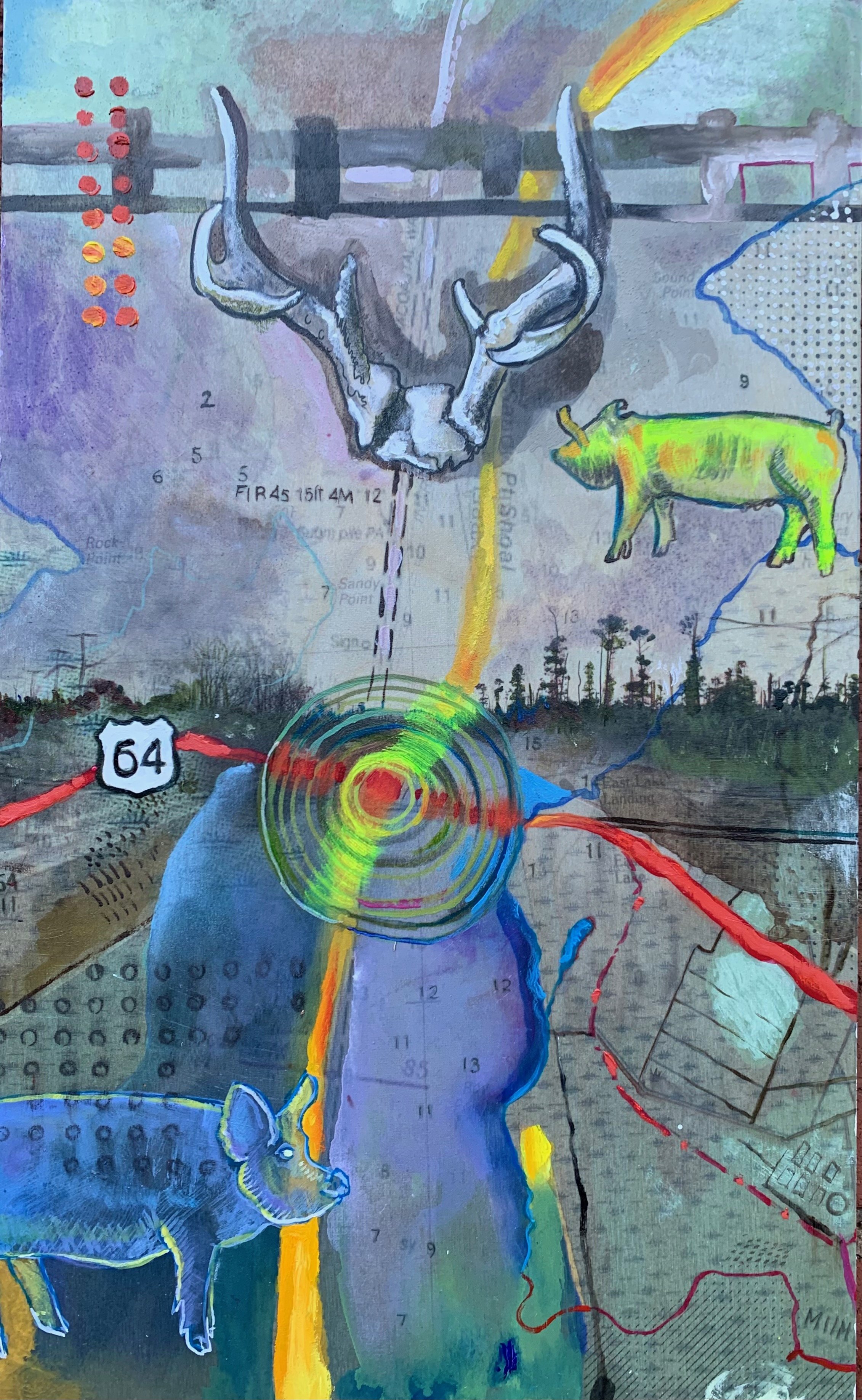

Highway 64 winds its way across the United States from Four Corners in Arizona to Whalebone Junction in North Carolina. Highway 64, built in the 1930s, crosses the Suffolk Scarp, which follows Highway 32 from Plymouth to Acre Station. The scarp is a paleoshoreline that used to meet the ocean. If you travel east on the two lanes of Highway 64 from Plymouth, you will pass dense forests of pine and sweet gum and fields fallow or fertile with soybeans, cotton, and corn. These fields used to be filled with tobacco. There are also miles of low-rise metal buildings, evidence of concentrated animal feeding operations, and dirt roads. In Tyrell County, you will eventually cross the Alligator River Bridge, built in 1962 and officially named after Lindsey C. Warren, a staunch segregationist and an influential politician who blocked the ratification of the 19th amendment in North Carolina. The aging bridge is nearly three miles long and made of concrete covered at points in a low shag of green moss. The swing bridge not only connects Tyrell County to Dare County from east to west but also is the gateway from the Albemarle Sound to the Alligator River from north to south. In 2024, construction will begin on a new high-rise bridge.

4

On the other side of the bridge is Dare County. Named for the first English child born on Roanoke Island, now the home of the “Lost Colony.” Virginia Dare was transformed into a white doe by a jealous suitor, Chico. It is a legend that her ghost, an elusive white deer, haunts the woods on Roanoke Island and can be seen between midnight and dawn. Dare is one of the richest counties in North Carolina; despite this, Dare County has never been an easy place to live, especially for those people who are not affluent.

5

The peninsula between the Alligator River and the Pamlico Sound is a patchwork of pecosins, bogs, swamp forests, dunes, and salt marshes. Snaking parallel to the narrow two-lane road are a network of black ditches filled with reeds, rotting vegetation, brown, green and red algae, alligators, and mats of floating vegetation. Residents built the ditches to divert water away from certain patches of land to improve the prospects for forestry and farming. Over time, these waterways have begun to have the opposite effect. In combination with prolonged droughts and unpredictable hurricanes like Hurricane Irene. They have become arteries for saltwater intrusion.

6

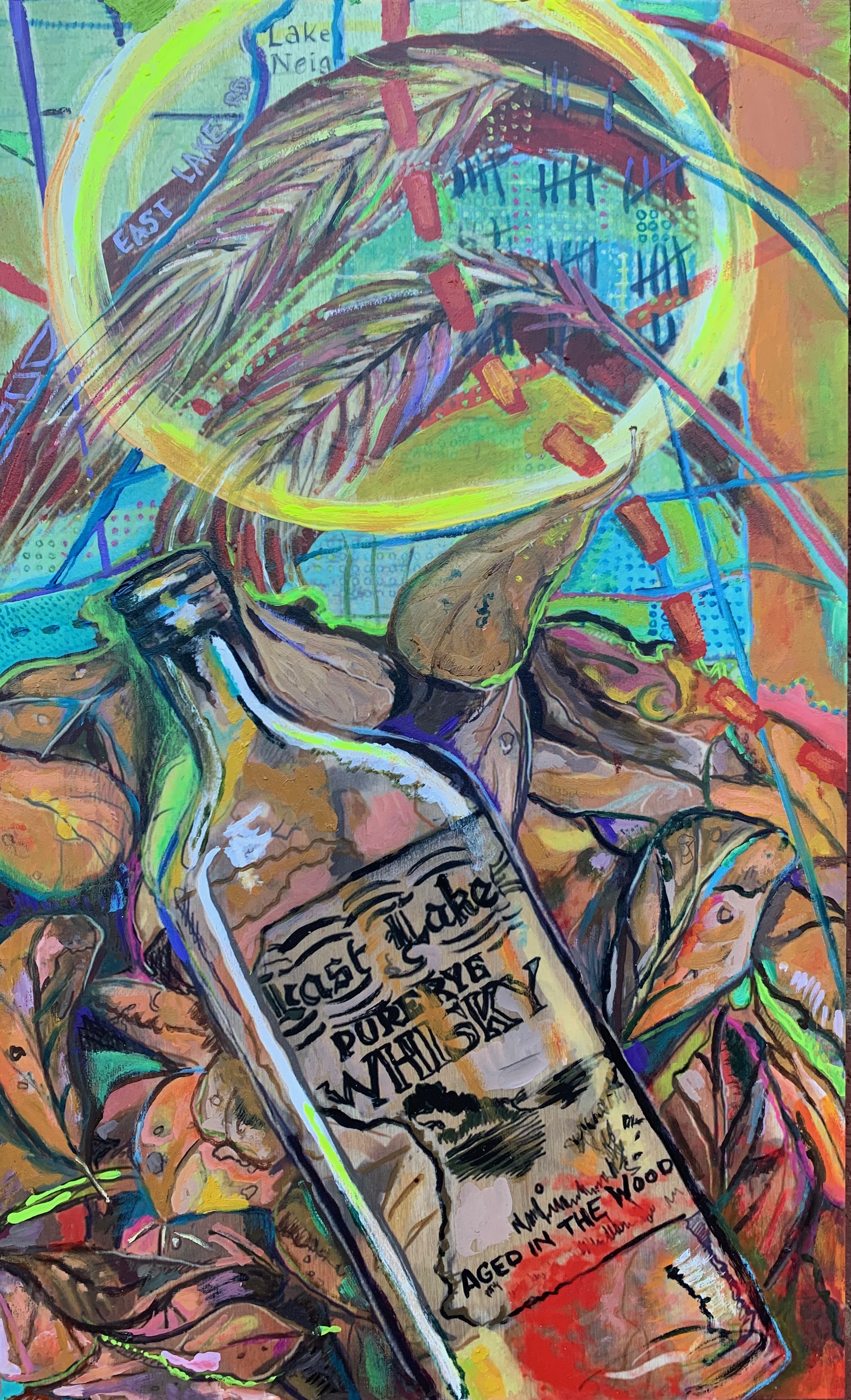

East Lake is the first town you enter in Dare County. It was once the home of East Lake Moonshine. The brew that resulted from farmin’ in the woods was reportedly sought after and smooth. The bootleg distillers used rye instead of wheat. North Carolina was a dry state from 1908 until 1937. Bootlegging was profitable for making ends meet after all the timber was cut. In present-day East Lake, the major businesses include a crematorium, a seasonal haunted house, a lumber company, a machine painting business, and a few churches. The last census recorded 124 people. The median age was 70.

7

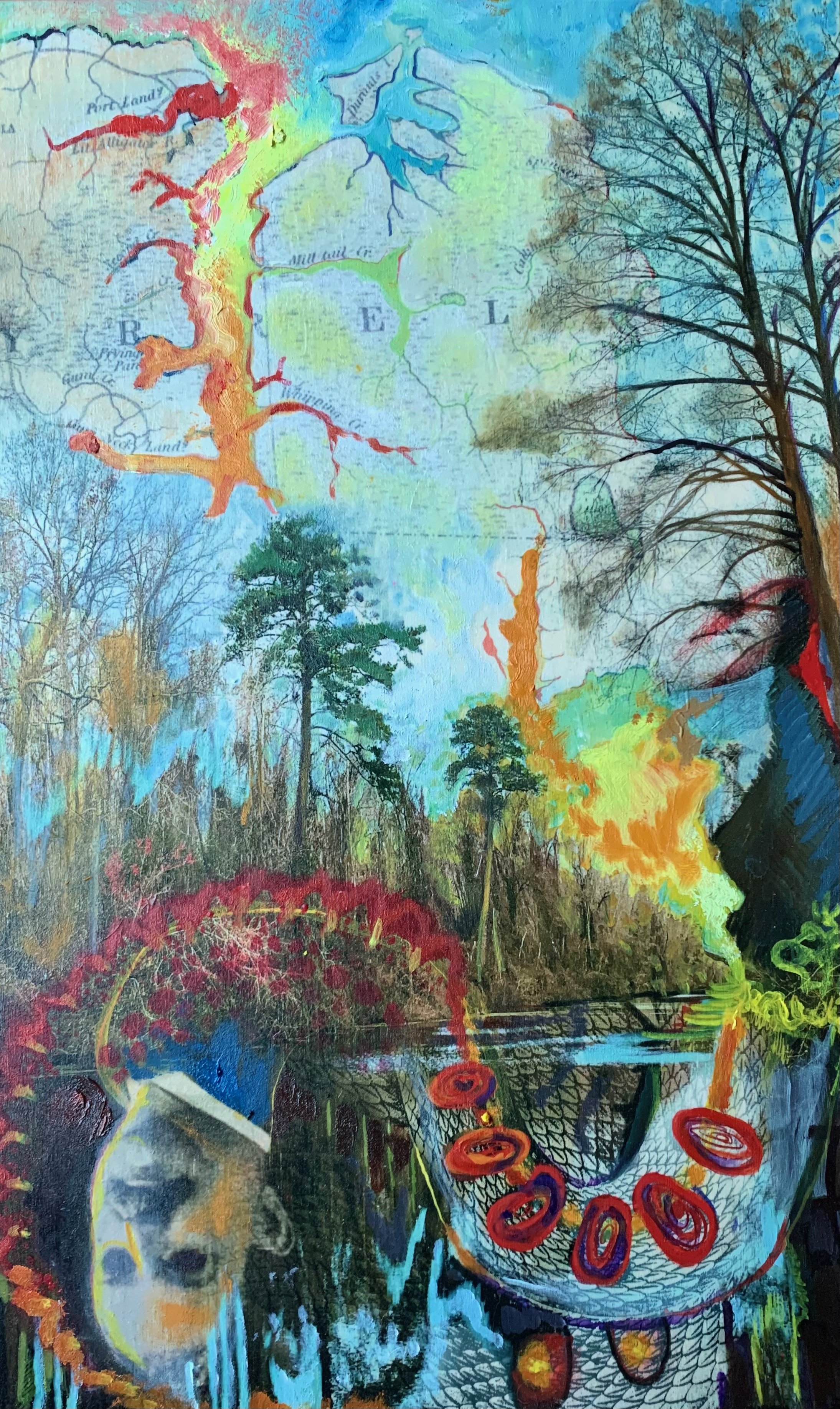

Suppose you veer off 64 and head south on Buffalo City Road into the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. In that case, you will eventually find yourself along the shores of Mill Tail Creek and at the former site of Buffalo City. Buffalo City is a ghost town. The rot and boggyness of the ground have left little evidence of its existence. It was settled by Russians and African Americans in 1888 after the Civil War as part of a lumber company funded by Frank and Charles Goodyear. The Russians and African Americans lived in rows of white-washed houses, and the white families in red bungalows. At the height of the logging heyday, approximately 3000 people were living in Buffalo City (Boldaji, 2016). The men logged juniper and cypress. There was no sewage, electricity, or running water. The street, made of lumber and sawdust, was divided by a railroad used to bring logs from the woods to the mouth of the creek. By 1940 Buffalo City was defunct.

8

In the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, survival is still a questionable business for most species. Bear, waterfowl, and deer are plentiful, but the red wolf, the red-cockaded woodpecker, and the American alligator are all species threatened by Anthropogenic actions of humans. These actions have helped to lend energy to superstorms, tidal surges, and saltwater intrusion. The refuge is home to a pack of red wolves. They were first identified as threatened by extinction in 1966. By 1980 there were no more wild red wolves left in the world. Through captive breeding sponsored by the Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium in Washington state, the population was saved. They were introduced into the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in 1987. At one time the population was 120. Due to human-caused mortality, the population in North Carolina has rapidly declined. The Eastern North Carolina Red Wolf pack, consisting of less than 25 animals, is the only wild population in the world. The oldest known red wolf on record, 1743F was found dead in June of 2023. She was 14.

9

When the fields in the refuge are fallow or freshly harvested, it is not uncommon to see large flocks of waterfowl like the majestic white Tundra Swans. There are over 250 species of birds in the refuge. A visitor in the winter with a bit of luck might encounter a rare northern Saw-whet owl or, in the summer, a black-billed cuckoo. The southern habitats of both birds have been shrinking due to the dark specter of climate change. People come to the refuge not only birdwatch or catch a rare glimpse of wildlife like bears, wolves, and birds but to kill. Ducks, geese, coot, quail, mourning doves, snipe, woodcock, rabbits, squirrel, and white-tailed deer make plentiful prey. The state also allows the hunting of Opossums and raccoons just before sunrise and just after sunset. People traditionally stuff and roast possums with sweet potatoes in the fall. According to the early versions of The Joy of Cooking, it is best to trap them alive and fatten them up on milk and cereals for ten days before killing and eating them. (Winick, 2019). During the early 1900s, Opossum dinners became a racial spectacle in the Jim Crow South. According to Stephanie Bryan, a Professor at Emory,

Since the antebellum era, white males of southern plantation

households would occasionally oversee or accompany

enslaved people's nighttime opossum hunts, claim their spoils,

and then relegate the game's preparation to African American

cooks. Drawing on this tradition, a generation of white men

with rural upbringings came to see opossum hunts as a means

of perpetuating antebellum culture by reinforcing and

reinscribing racial lines. They mocked and derided opossums as

indicative of negative aspects of African American culture while

simultaneously celebrating African Americans as possessing a

folk knowledge of hunting, preparing, and cooking opossums.

Other animals and plants are off limits to hunters, foragers, and visitors. Snakes are beautiful, elusive, and plentiful including three venomous species, the cottonmouth, Timber Rattlesnake and the copperhead.

10

The Alligator River refuge harbors a thick mat of bogs, shrubby pond pines, and cypress trees. The majestic cypress trees have been called sentinels of the swamp. They are the oldest known tree species in the Eastern United States. Located roughly 120 miles as the crow flies in the Black River in South Carolina is a Bald Cypress that is almost 2700 years old. These trees hold hundreds of years of climate data in their rings. Cypress forests were nearly logged out of existence; they are prized because the wood is insect and rot-resistant. In the refuges, underneath the thinning canopy of black gum, pond pines, holly, bay bushes, and cypress are pitcher plants, sundews, and low bush cranberries. In all the literature linked to the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, readers are warned repeatedly not to stray off the roads into the treacherous swamps to hike or hunt. While the landscape calls, it is essential to remember that the forest is shifting and possibly treacherous.

11

Instead of the thick fantastic non riverine forests of my childhood that were there even twenty years ago there are stark pale trunks and stunted shrubby pond pines. The pale, topless trunks are signs that the forest is haunted by salt. They are like white, irregular obelisks, a cypress, pine, and juniper graveyard. Fittingly, scientists have coined forests like the ones you see in the refuge ghost forests. If you leave the refuge and continue to wind your way around the peninsula on highway 264 south, the curse of salt is even more pronounced. The woods along the lonely stretch of black top are post-apocalyptic. They have been replaced by miles of salty marshland. Some segments have burned, young pond pines are scattered among the reeds, and the delicate pale markers of the ghost forests are blackened. In fifty years, much of this area will be marsh.

12

There is little that we can do to reverse the damage which has caused rapid climate change. It is an admirable fool’s errand to try and save the sentinels of the swamps along the Albemarle, Croatan, and Pamlico Sounds. Cypress trees grow incredibly slow, and their cones must dry out completely before they will release their seeds. Despite this, desperate optimists are planting oyster reefs and experimenting with salt-resistant trees in the hopes that the effects of salt intrusion can be slowed and that the spread of ghost forests will cease. If climate change continues to progress along the trajectory started and accelerated by humans during the Anthropocene the oceans will rise, the seas will warm, storms and periods of drought will intensify, plagues will ensue, coastlines will shrink and shift, and habitats like the rare maritime forests along the sounds will die. When the forests die, carbon is released, hundreds of species will lose their habitats, and as the oceans warm and summers last longer and longer and become hotter and hotter, native fish populations will shift and die, algae will bloom, consuming the oxygen, their green and red carpets fueled by nitrogen and phosphorous. The only thing that will truly preserve the environment as it currently exists and end ghost forests is time and the extinction of humans. If the population of humans thins or ceases to exist entirely, the planet will continue to spin, tides will be called to, and from the shores by the moon, silvery marsh grasses will whisper when the wind blows, and the forests will evolve.

Bibliography

Aguilos, M., Brown, C., Minick, K., Fischer, M., Ile, O. J., Hardesty, D., ... & King, J. (2021). Millennial-scale carbon storage in natural pine forests of the north carolina lower coastal plain: Effects of artificial drainage in a time of rapid sea level rise. Land, 10(12), 1294.

Aguilos, M., Warr, I., Irving, M., Gregg, O., Grady, S., Peele, T., ... & King, J. (2022). The Unabated Atmospheric Carbon Losses in a Drowning Wetland Forest of North Carolina: A Point of No Return?. Forests, 13(8), 1264.

American community Survey, Census Reporter.(2023). “East Lake Township, Dare County, NC.” Last accessed February 19, 2023, https://censusreporter.org/profiles/06000US3705590

964-east-lake-township-dare-county-nc/.

Arner, R. D. (1978). The Romance of Roanoke: Virginia Dare and the Lost Colony in American Literature. The Southern Literary Journal, 5-45.

Barber, W. (Bill) (2020). Buffalo City & the Blount Patent: A History of Logging the Dare Mainland. Lulu Press.

Barrett, B. (2019). Climate Change in a Coastal County: Think Global, Act Hyperlocal. Stateline, Pew Charitable Trust. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/07/26/climate-change-in-a-coastal-county-think-global-act-hyperlocal

Bryan, S. (2022). The Emblem of “North American Fraternity": Opossums and Jim Crow Politics. Southern Spaces. (October 22).

https://southernspaces.org/2022/emblem-north-american-fraternity-opossums-and-jim-crow-politics/

Boldaji, A. (2016). Ghost Town: The Forgotten Story of Dare county’s Buffalo City. North Beach Sun (April 20). https://www.northbeachsun.com/ghost-town-the-forgotten-story-of-dare-countys-buffalo-city/

Cotten, S. S. (1901). The White Doe: The Fate of Virginia Dare; an Indian Legend. JB Lippincott.

Edwards, Justin, Graulund, Rune, and Höglund, Johan.(2022). Dark Scenes from Damaged Earth: The Gothic Anthropocene. The University of Minnesota Press.

Jukowitz, Mark. 2022. “Dare’s housing costs, Hyde’s poverty rate highlighted in new report.” Island Free Press, June 29, 2022.

Martinez, M., & Ardón, M. (2021). Drivers of greenhouse gas emissions from standing dead trees in ghost forests. Biogeochemistry, 154(3), 471-488.

McDermott, A. (2023). Ghost forests haunt the East Coast, harbingers of sea-level rise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(38), e2314607120.

Morrison, J. (2019). “North Carolina Bald Cypresses Are Among the World’s Oldest Trees.” Smithsonian Magazine, May 19, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science

-nature/north-carolina-bald-cypresses-among-worlds-old est-trees-180972134/.

Parkin, S. M. (2019). Reconstructing Buffalo City (1887–1986): Applying Archaeological Site Reconstruction Technique to a North Carolina Maritime Entrepot. East Carolina University.

Rountree, H. C. (2021). Manteo's World: Native American Life in Carolina's Sound Country Before and After the Lost Colony. UNC Press Books.

Senter, J. (2003). Live dunes and ghost forests: Stability and change in the history of North Carolina's maritime forests. The North Carolina Historical Review, 80(3), 334-371.

Simpson, B. (2000). The Great Dismal. Univ of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

Smart, L. S., Taillie, P. J., Poulter, B., Vukomanovic, J., Singh, K. K., Swenson, J. J., ... & Meentemeyer, R. K. (2020). Aboveground carbon loss associated with the spread of ghost forests as sea levels rise. Environmental research letters, 15(10), 104028.

Stephenson Jr, F., & Mulder, B. N. (2017). North Carolina Moonshine: An Illicit History. Arcadia Publishing.

Ury, E. A., Yang, X., Wright, J. P., & Bernhardt, E. S. (2021). Rapid deforestation of a coastal landscape driven by sea‐level rise and extreme events. Ecological applications, 31(5), e02339.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2023). “Red Wolf Recovery

Program.” Last accessed February 19, 2023,

https://www.fws.gov/project/red-wolf-recovery-program.

Carmichael, M. J., & Smith, W. K. (2016). Standing dead trees: a conduit for the atmospheric flux of greenhouse gases from wetlands?. Wetlands, 36(6), 1183-1188.

Winick, S. (2019). “A possum crisp and brown: The opossum and American foodways.” Library of Congress, August 15, 2019, https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2019/08/a-possum- crisp-and-brown-the-opossum-and-american-foodways

All sound effects and music for the sound piece were downloaded with a subscription from Artlist

LIC Pw5wqw

artlist.io/

Music and Sound effects by: Enzo Bellomo, OP Baron, Victor Dance Orchestra, Yonata Riklis, Tiko Tiko,Hagai Davidoff, Mark Grundhoefer, Felix Blume, RZ Post, Ivo Vicic, West Wolf, Shirley Spikes, D Fine Us, AMUSIA, Ardie Sun, Hilltop Trio, Francesca D'Andrea, Ziv Moran, Mischa Elman, Ben Reneer, Downtown Binary, Tomer Ben Ari, Eneas Mentzel, Mat Eric Hart, Articulated Sounds, Carlos Santa Rita, and Nic Macmahan.