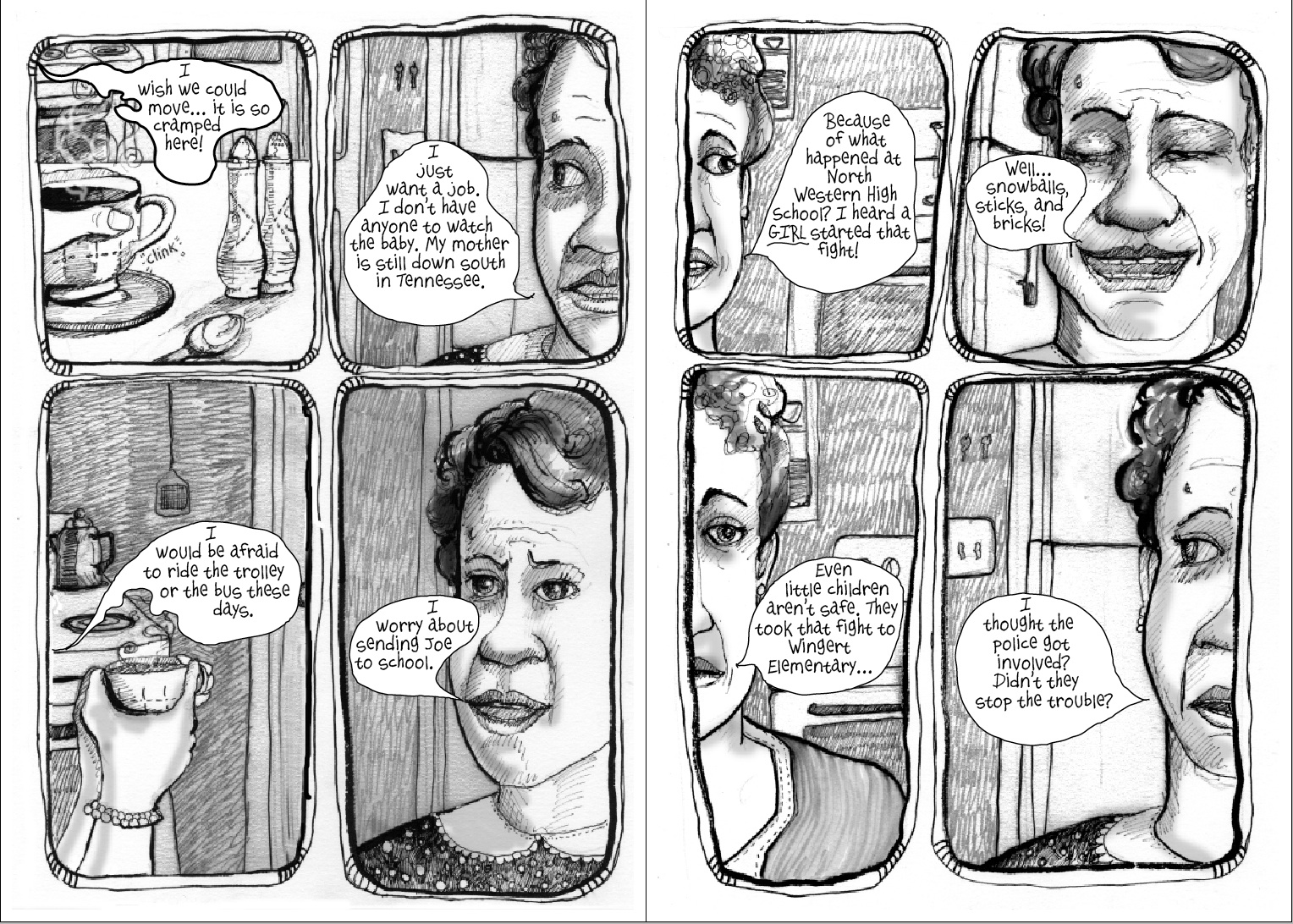

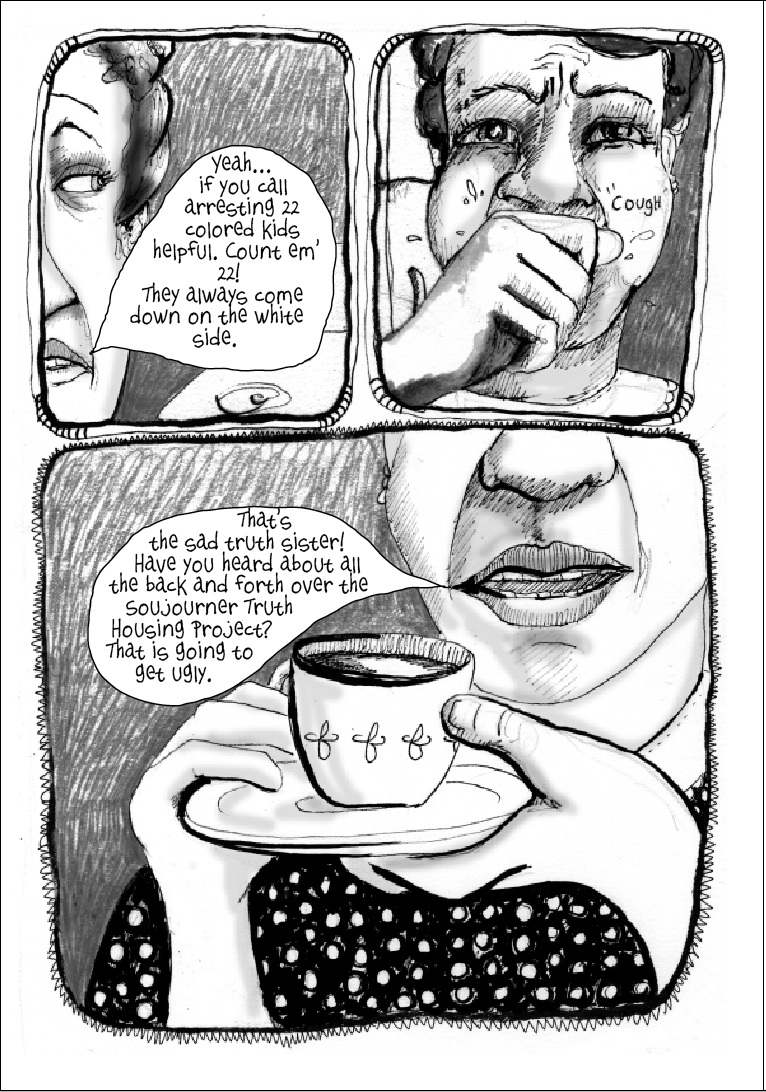

Run Home If You Don't Want To Be Killed: The Detroit Uprising of 1943

This year I am going to work on a multi year research project about the 1943 Detroit Rebellion. The final product will be published in 2021 as a graphic novel, Run Home If You Don't Want To Be Killed: The Detroit Uprising of 1943, by University North Carolina Press and the Duke Center for Documentary Studies.

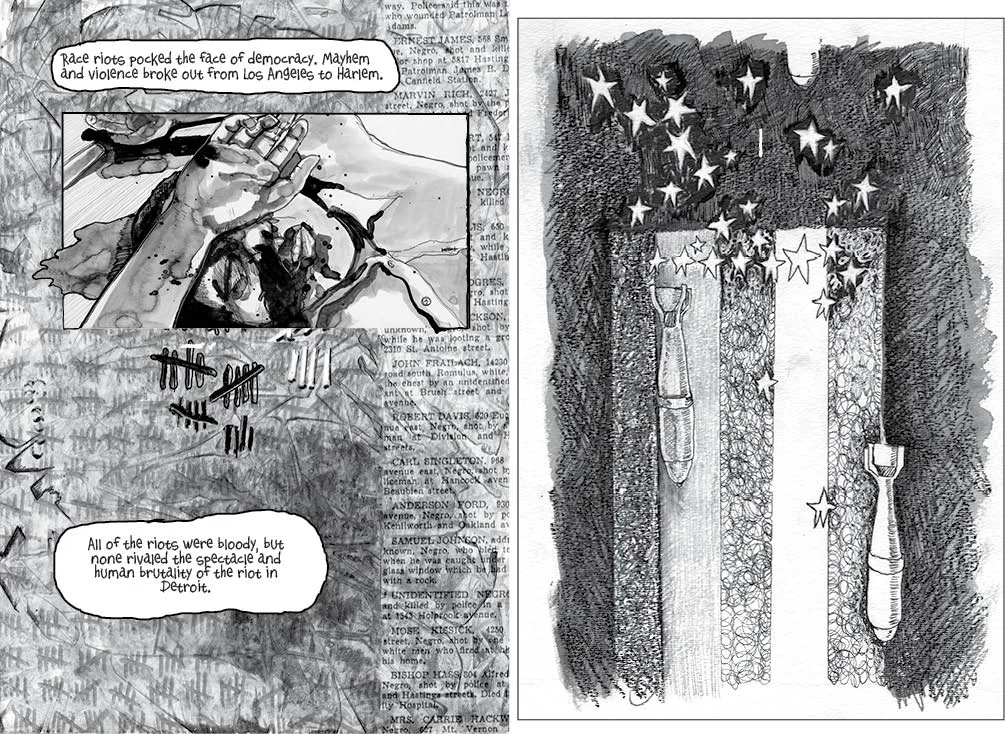

Run home if you don’t want to be killed: The Detroit Uprising of 1943 is a graphic history based on a series of events that led to the worst race riot in 1943 in the United States. This graphic history is a hybrid text composed of stories, history, and images; it is designed to challenge people’s assumptions about, race, culture, and violence in the United States during World War II. In 1943 there were approximately 242 disturbances that were racially motivated in 48 different cities throughout the country. The uprising that occurred in Detroit was the worst from that year.

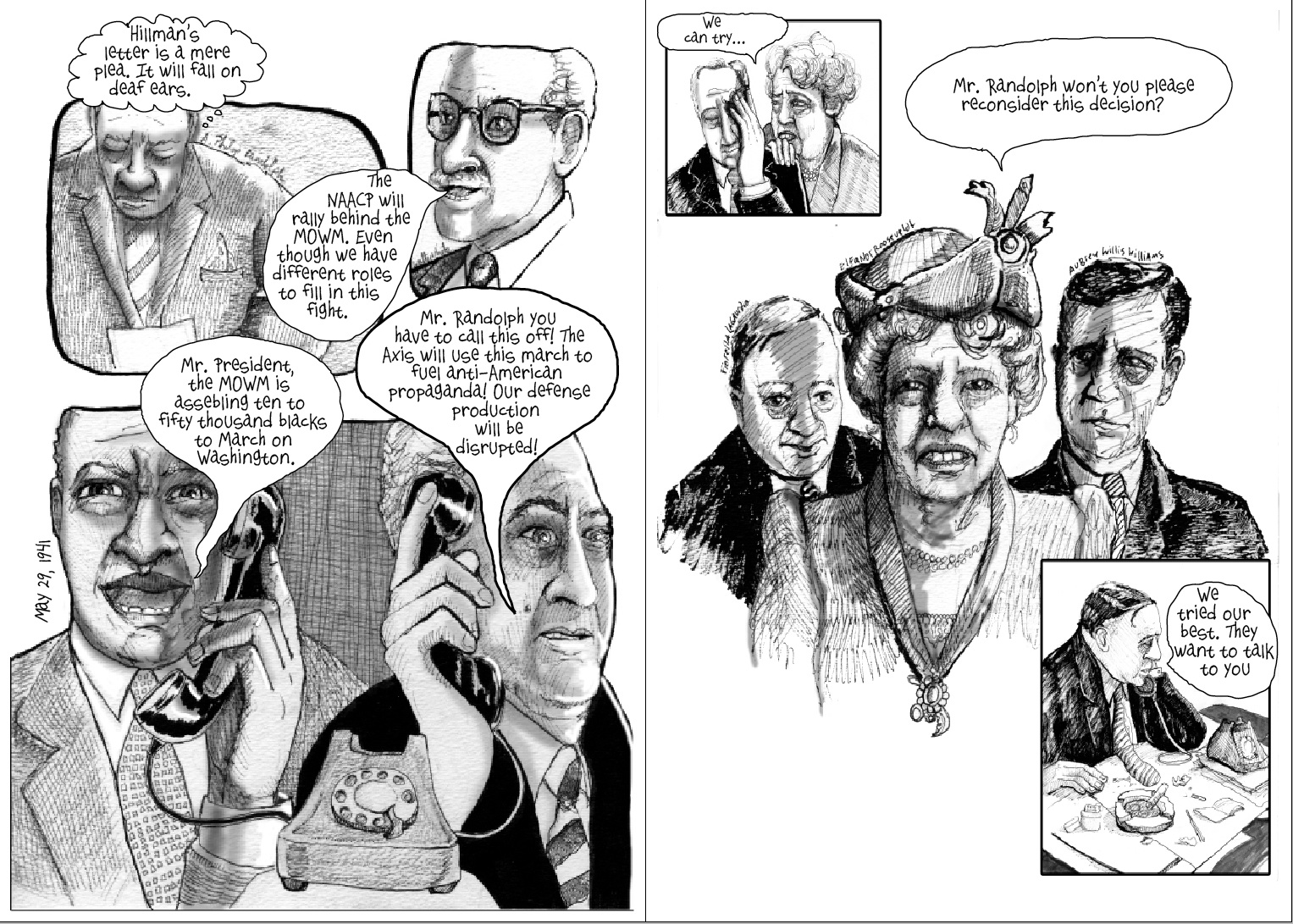

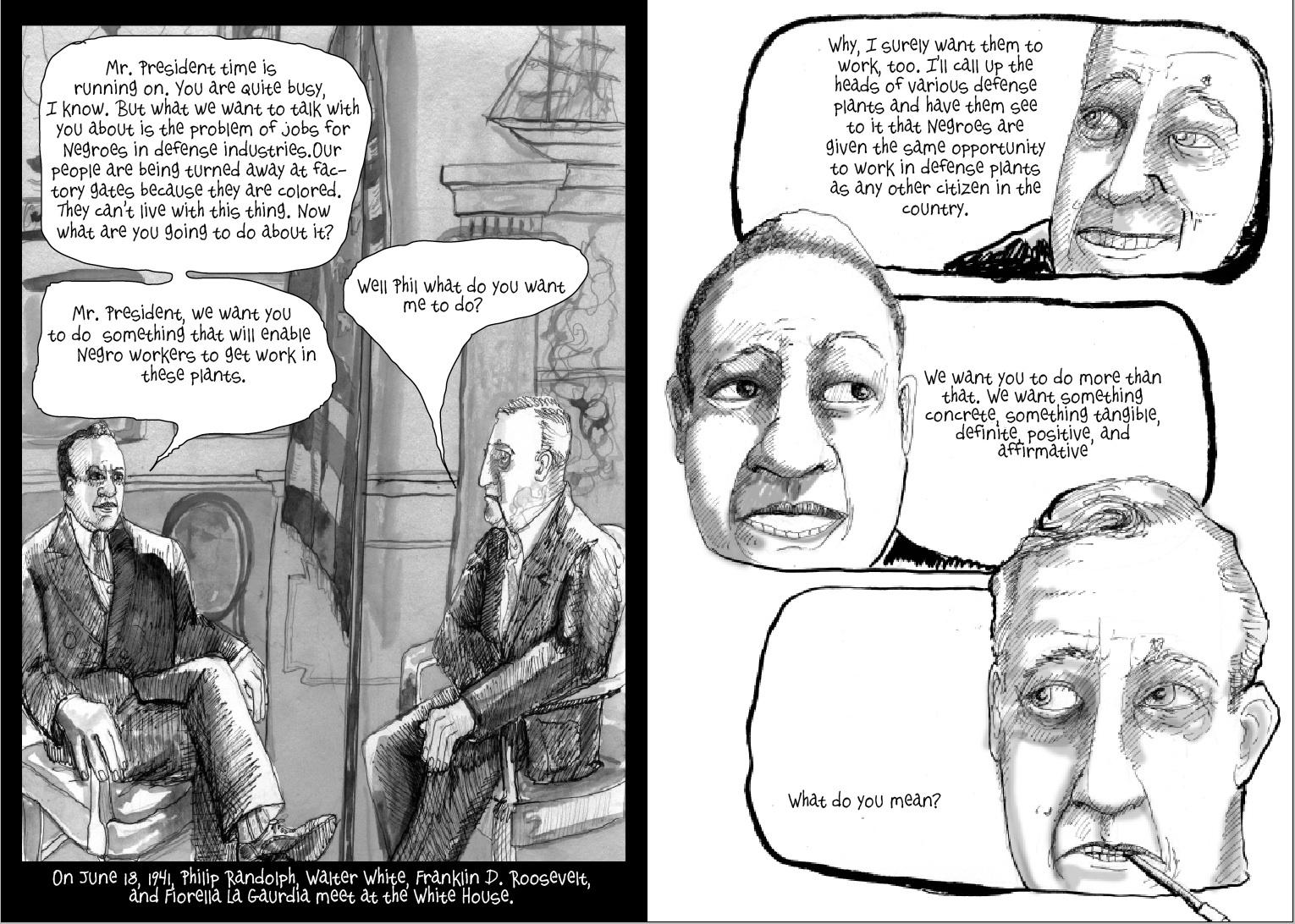

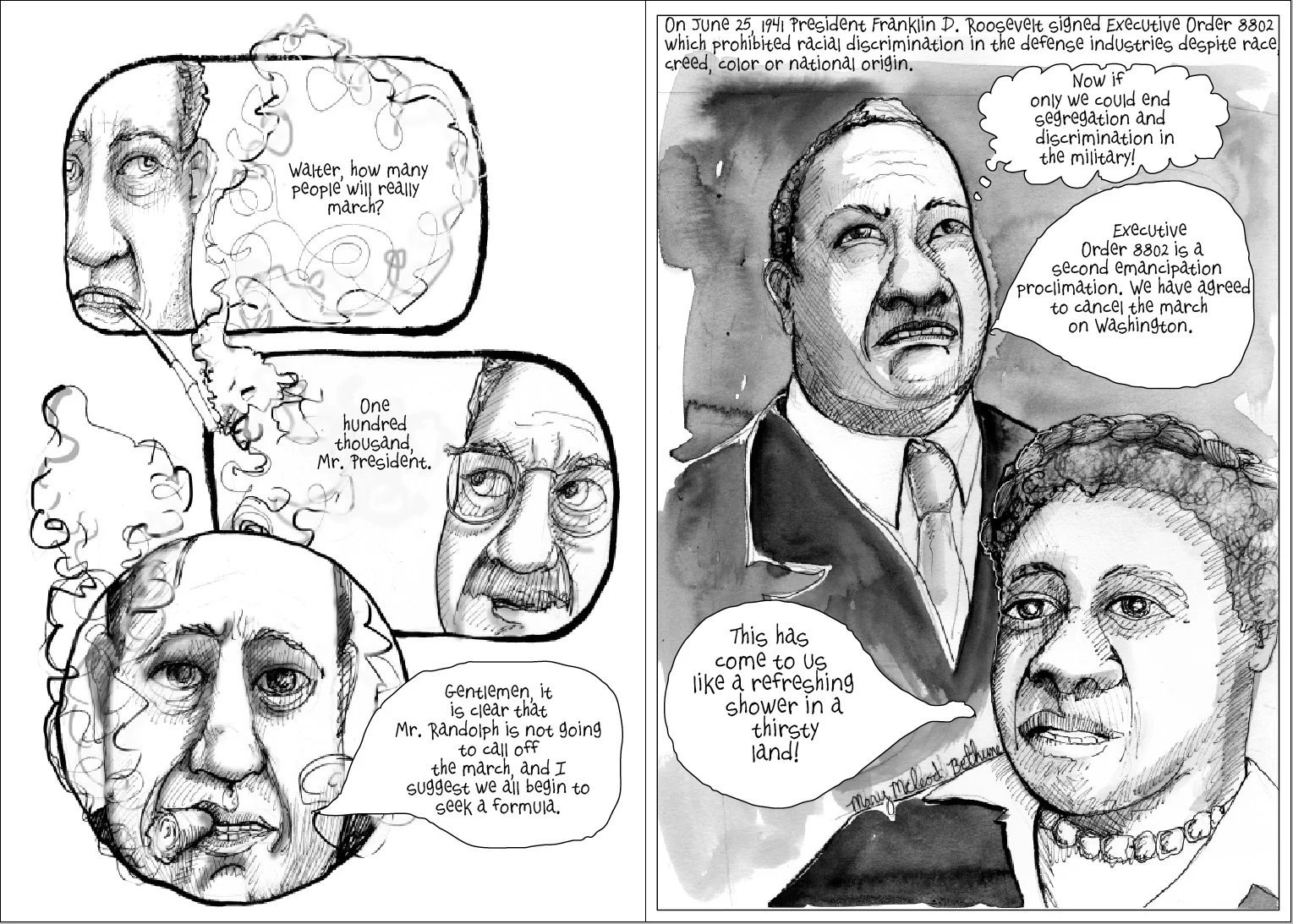

In the story of Detroit in 1943 the unfolding events of the uprising offer an image of the social, economic, and cultural pressures that gave way to violence at the end of World War II and the beginning of the American Civil Rights movement. The lack of decent housing, racist rhetoric, police brutality, chivalry, and lack of organization for newly arriving workers created a firestorm of violence. This was compounded by the double standard of governmental efforts during World War II to achieve freedom from oppression abroad while still maintaining a racist system of apartheid in the United States. In Detroit, of the 185 wartime plants 55 of them would hire no African Americans. The police force in Detroit was made up of 3400 officers; only 43 were black.

In the wake of the riot the official report co-authored by the Detroit Police Commissioner blamed only African Americans for the disturbance (Langlois, 1983). The entire country had been watching the powder keg of Detroit, the nation’s fourth largest city at the time, for over a year. Everyone knew that sooner or later there would be a major racial disturbance, yet nothing was done. Even after the riot began, the municipal government would not declare martial law or call in the National Guard until nearly 30 hours of terror had passed.

The 1943 Detroit rebellion is a significant story. This was the most violent and largest riot that took place during World War II. The unguarded racism, economic competition between blacks and whites, and the ways that our country shifted as a result of urban opportunities and capitalism are invisible in most popular depictions of World War II. The riots during World War II signaled the beginning of an organized racial sea change. In Detroit they came on the heels of Dr. Ossian Sweet’s struggle over discriminatory housing practices, the Sojourner Truth Housing Project debacle, and prior to another giant riot in 1967 known as the 12th street riot.

There are many scholarly books, which mention the Detroit Riot of 1943, like The Origins of The Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Post War Detroit by Thomas Sugrue (Princeton University Press) but only a handful explore it as a subject worthy of lengthy scholarly analysis. The most recent titles include, Layered Violence: The Detroit Rioters by Dominic J. Capeci Jr and Martha Wilkerson (1991) published by the University Press of Mississippi, Alfred McClung Lee and Norman Humphrey’s original account, Race Riot and later expanded version also named Race Riot published respectively in 1943 (The Dryden Press) and in 1968 (Octagon Books), also A Study in Violence: The Detroit Race Riot by Robert Shogan and Tom Craig, published in 1964 by Chilton Company. There have also been numerous articles that focus on various subjects tied to the riot including rumor, gender, police violence, and the typology of riots.

The form of the graphic narrative would allow this text to re-populate the imaginations of readers with images and stories that are historical, political, and aesthetic. While the form of a graphic narrative is too short to allow for a deep written explanation of new scholarship on the riot, this text can offer a rich reading experience about the nexus of class, race, and gender, through a compelling story of historical significance. The images within the text offer a glimpse into life and culture in 1943, embody stories with history and images of those who lived through it, and include some never before published photographs from the Detroit Free Press and hundreds of original drawings. This cutting-edge approach would add to the existing scholarship on this event by illuminating the voices of women who were affected, and by interpreting the event through images, text, story, and design in a way that has never been attempted by other scholars. Images and design provide rich details to readers on multiple levels beyond what text alone can say. Events in a single experience can be placed on one page interrupting the traditional chronology. According to Alyson King (2012), For historical narratives, then, a graphic architecture:

opens the door for new configurations of the relationship between chronology, narrative line, and time-sequence. The two-dimensionality of the comics page can be used to allow a single group of panels to be read simultaneously in more than one linear sequence, calling into question the very idea of a single narrative line. (Said, 2007)

The graphic novel and comic formats, therefore, disrupt and undermine the linear and chronological way in which historical narratives have usually been told.